Risk estimators¶

Risk has always played a very large role in the world of finance with the performance of a large number of investment and trading strategies being dependent on the efficient estimation of underlying market risk. In this regard, one of the most popular and commonly used representation of risk in finance is through a covariance matrix – higher covariance values mean more volatility in the markets and vice-versa. Covariance matrix is the most commonly used risk model, as it describes asset volatilities and their co-dependence in terms of quadratic forms. This is important because one of the principles of diversification is that risk can be reduced by making many uncorrelated bets (correlation is just normalised covariance). This also comes with a caveat – empirical covariance values are always measured using historical data and are extremely sensitive to small changes in market conditions.

Interestingly enough, a piece of research by Kritzman et al. (2010) 1 shows that minimum variance portfolios may perform better out of sample than the equally weighted portfolio.

This makes the covariance matrix an unreliable estimator of the true risk calling for the need of better estimators. In this section we devote our analysis to presenting different covariance matrix estimators which aim to reduce the estimation risk.

Asset allocation and risk assessment also rely on correlations (covariance), however in this case a large number of correlations are often required. Construction of an optimal portfolio with a set of constraints requires a forecast of the covariance matrix of returns. Similarly, the calculation of the standard deviation of today's portfolio requires a covariance matrix of all the assets in the portfolio. These functions entail estimation and forecasting of large covariance matrices, potentially with thousands of assets.

Risk estimator base class¶

The class BaseRiskEstimator is at the core of all risk estimators.

The .fit method takes either price data or return data, depending on the initialization parameter returns_data.

Moreover, you can always modifiy the parameter with the .set_returns_data(True|False) method, returning a new estimator.

With the generic term risk we mean a proxy measure of portfolio risk, like the portfolio volatility as measured from the standard deviation, the Mean-Absolute-Deviation of the excess returns, or the conditional value at risk.

Warning

For all covariance-based estimators, keep in mind that objects are supposed to be fed with daily prices or returns, and annualized covariances are returned.

Indeed, default annualization factor is 252 periods, the approximate number of business days in a year.

If returns have a different frequency, and covariance over different time periods is required, you must modify the frequency parameter.

For example if you are feeding price tickers at a 30 minute time-frame, and you need to compute weekly covariance, you need to specify the frequency factor as the number of units of periods in the covariance interval.

In that specific case frequency=2*24*7=336.

Keep in mind though that for returns with frames shorter than one day, strong serial correlation may exist, making this covariance aggregation approximation incorrect.

For more details see the paper from Andrew Lo 4.

For notation, please see the notation section

Sample Covariance SampleCovariance 📖¶

Sample covariance from the asset returns.

For more information about the covariance estimator implemented here see the scikit learn page on covariance estimation.

The SampleCovariance is obtained from the asset returns \(r_t^{(i)}\) for \(i \in 1,\ldots,N\) as follows:

Semicovariance SemiCovariance 📖¶

The semicovariance, a.k.a. the covariance matrix estimated from only the returns exceeding a given benchmark \(b\) (typically 0). We adopt the definition as from pyportfolioopt. There are multiple possible ways of defining a semicovariance matrix, the main differences lying in the 'pairwise' nature, i.e whether we should sum over \(\min(r_i,B)\min(r_j,b)\) or \(\min(r_i r_j,b)\). In this implementation, we have followed the advice of Estrada (2007) 3, preferring:

CovarianceRMT CovarianceRMT 📖¶

The random matrix theory (RMT) postulates that a covariance matrix is built from a component related to bulk random gaussian noise and from a real signal, as described from the Marchenko-Pastur distribution. Here we follow the approach from MacMahon and Garlaschelli 5. The calculation is based on the idea that a signal eigenspectrum consists in a continuos bulk and a "market-mode", to filter. Basically, the deviation of the spectra of real correlation matrices from the RMT prediction provides an effective way to filter out noise from empirical data. Starting from the eigendecomposition of the sample covariance

\begin{equation}

\hat{\boldsymbol \Sigma} = \sum_{k}^N \lambda_k \mathbf{q}_k \mathbf{q}_k^T

\end{equation}

where \(\lambda_k\) is the \(k\)-th eigenvalue and \(\mathbf{q}_k\) is the \(k\)-th eigenvector of the sample covariance matrix, we get the filtered covariance matrix as:

The Marchenko-Pastur distribution postulates that it is possible to set a specific limit for the eigenvalues falling outside the bulk of random noise \(\lambda_{\textrm{MP}}\). Beyond that value, the effect of random gaussian noise is minimum and "true" signals are compared.

We refer the reader to the paper 5 for more details, or looking into the scikit-portfolio documentation.

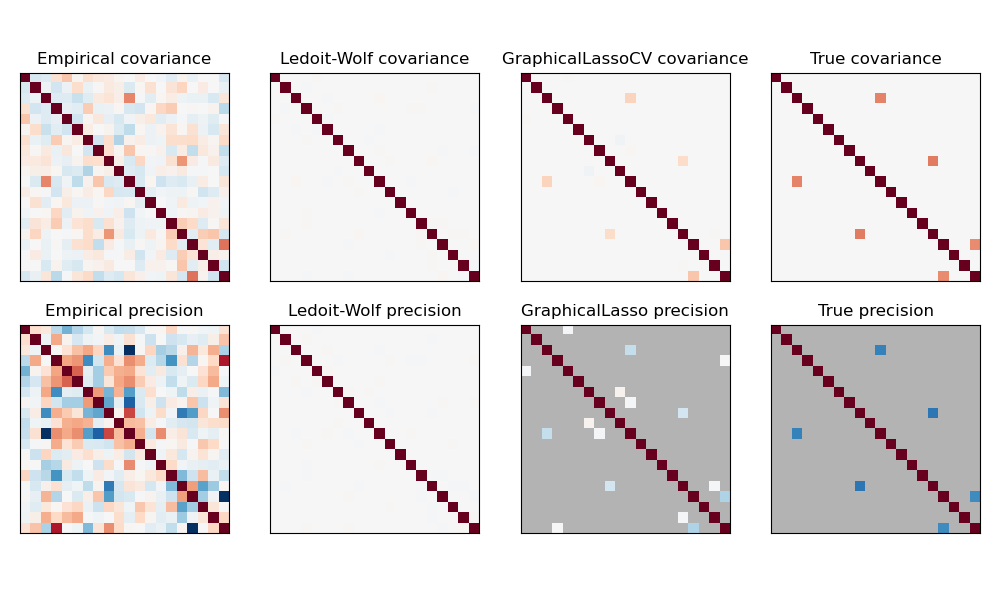

Ledoit-Wolf covariance estimator CovarianceLedoitWolf 📖¶

One popular approach to dealing with estimation risk is to simply ignore parameters that are hard to estimate. A popular approach is thus to employ "shrinkage estimators" for key inputs. For example, Ledoit and Wolf (2004)2, propose shrinking the sample correlation matrix towards (a fancy way of saying "averaging it with") the constant correlation matrix. The constant correlation matrix is simply the correlation matrix where each diagonal element is equal to the pairwise average correlation across all assets.

Mathematically, this shrinkage consists in reducing the ratio between the smallest and the largest eigenvalues of the empirical covariance matrix. It can be done by simply shifting every eigenvalue according to a given offset, which is equivalent of finding the L2-penalized Maximum Likelihood Estimator of the covariance matrix. See scikit-learn documentation for more details. In practice, shrinkage boils down to a simple a convex transformation:

Specifically, Ledoit-Wolf is a particular form of shrinkage, where the shrinkage coefficient \(\alpha\) is computed using the formula described in 2.

Covariance GLASSO CovarianceGLASSO 📖¶

The GLASSO covariance method estimates the true covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol \Sigma\) by solving the following optimization problem in the precision matrix \(\boldsymbol \Theta\) with a L1 regularization term, inducing sparsity in the recovered precision matrix:

\begin{equation} \underset{\boldsymbol \Theta \succeq \mathbf{0}}{\textrm{argmin}} \left\lbrack \textrm{Tr}(\hat{\boldsymbol \Sigma} \boldsymbol \Theta) - \log \det(\boldsymbol \Theta) + \lambda \sum_{i,j} | \Theta_{ij} |\right \rbrack \end{equation} The latter is a convex optimization problem in \(\boldsymbol \Theta\).

More details here and in the original paper by Tibshirani et al 6.

Exponential Moving Average Covariance CovarianceExp 📖¶

This method of computing the covariance takes into account with an exponential moving average only the most recent observations, given a decay factor governed by the parameter span.

Given a temporal span parameter \(K\) the tensor \(\mathbf{Q} \in \mathbb{R}^{T \times N \times N}\) is obtained as:

Finally, an exponential moving average is performed on \(\mathbf{Q}\) over the temporal dimension \(t\):

where \(\alpha\) is the decay factor \(0\leq \alpha \leq 1\) uniquely specified by the span factor as \(\alpha = 2/(\textrm{span}+1)\) for \(\textrm{span}\geq 1\).

Hierarchical filtered covariance: average linkage 📖¶

Hierarchical filtered covariance: complete linkage 📖¶

Hierarchical filtered covariance: single linkage📖¶

References¶

-

Kritzman, Page & Turkington (2010) "In defense of optimization: The fallacy of 1/N". Financial Analysts Journal, 66(2), 31-39. ↩

-

O. Ledoit and M. Wolf, "A Well-Conditioned Estimator for Large-Dimensional Covariance Matrices", Journal of Multivariate Analysis, Volume 88, Issue 2, February 2004, pages 365-411. http://www.ledoit.net/honey.pdf ↩↩

-

Estrada (2006), Mean-Semivariance Optimization: A Heuristic Approach ↩

-

Lo, A, "The statistics of Sharpe ratio". https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2469/faj.v58.n4.2453 https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v58.n4.2453 ↩

-

MacMahon M, Garlaschelli D., "Community detection for correlation matrices". Phys. Rev. X 5, 02100 https://journals.aps.org/prx/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevX.5.021006 ↩↩

-

Friedman, Jerome, Trevor Hastie, and Robert Tibshirani. "Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso." Biostatistics 9.3 (2008): 432-441. ↩